Parasites

Ectoparasites

There are a variety of organisms, both commensal and parasitic, that will hitch a ride on sea turtles.

Green turtles on the whole are very clean. If they bear a heavy epibiont load, it is indicative of disease.

Note: It is important to document in the record if the organisms are present on soft tissue or the hard tissue of the head/carapace/plastron.

Commensal Organisms

Sea turtles may carry: barnacles, crabs, shrimp, algae, bryozoans, oysters, bristle worms, polychaetes, brittle stars, and other organisms on their shells. Most of these organisms derive the benefit of transportation from the relationship .

Care must be taken (wear gloves!) when removing them, as some of these organisms can sting.

Information about where the turtle has been spending time can be obtained by determining the species of organisms found on the turtle. If unsure of species identification, photo document it for later review.

For example, most types of algae thrive in the intertidal zone and require high light. If they are present, it may be inferred that the patient was at the surface or in shallow water for extended periods of time. Some species of goose neck or stalked barnacles are pelagic (open-ocean).

Parasitic Organisms

Barnacles

All barnacles increase surface drag and decrease the overall hydrodynamic shape of the turtle. Barnacles can be pried off with a variety of tools, but care should be taken with those that have damaged the shell. These should be removed with care so as to not create further injury. All barnacles should be removed before radiographs are take as they will appear as radiodense masses that will confound interpretation.

There are 29 species of barnacles found on turtles. If all the barnacles present are of a similar size and species, it may be an indication that the turtle was inactive for a period of time.

Questions regarding the clinical significance of embedding barnacles arise frequently. "Stephanolepas muricata is a common symbiont of cheloniid sea turtles and it is most often found embedded between the scales along the leading edge of the fore flippers. It is relatively small, but appears more substantial on smaller turtles - like the hawksbill in the pictures. As with other turtle barnacles of the family Platylepadidae, S. muricata coaxes the skin of the turtle around the barnacle shell by producing elaborate projections that grasp the epidermis and stretch it around the barnacle. Often the turtle epidermis surrounding embedding barnacles will become cornified and scab like, or it will remain flexible, but uninjured. These barnacles do not pierce the skin of the host turtle, and any blood observed from the removal of these barnacles occurs from the methods used, or because the turtle's skin is torn when it is forcibly separated from the barnacle shell. Platylepadid barnacles do not bore into turtles in the traditional sense of the word 'boring', they embed themselves into host turtles as described above.

Questions regarding the clinical significance of embedding barnacles arise frequently. "Stephanolepas muricata is a common symbiont of cheloniid sea turtles and it is most often found embedded between the scales along the leading edge of the fore flippers. It is relatively small, but appears more substantial on smaller turtles - like the hawksbill in the pictures. As with other turtle barnacles of the family Platylepadidae, S. muricata coaxes the skin of the turtle around the barnacle shell by producing elaborate projections that grasp the epidermis and stretch it around the barnacle. Often the turtle epidermis surrounding embedding barnacles will become cornified and scab like, or it will remain flexible, but uninjured. These barnacles do not pierce the skin of the host turtle, and any blood observed from the removal of these barnacles occurs from the methods used, or because the turtle's skin is torn when it is forcibly separated from the barnacle shell. Platylepadid barnacles do not bore into turtles in the traditional sense of the word 'boring', they embed themselves into host turtles as described above.

Boring invertebrates typically secrete enzymes that destroy host tissue, which facilitates burrowing; or boring invertebrates will actively remove host tissue through the use of mouthparts or appendages. No specimens of turtle barnacles examined to date give any indication that these sea turtle symbionts possess the ability or physiology to 'bore' into turtles.

Boring invertebrates typically secrete enzymes that destroy host tissue, which facilitates burrowing; or boring invertebrates will actively remove host tissue through the use of mouthparts or appendages. No specimens of turtle barnacles examined to date give any indication that these sea turtle symbionts possess the ability or physiology to 'bore' into turtles.

Stephanolepas, and another deep-seated embedding barnacle Chelolepas cheloniae, appear to exploit wounds on host turtles - especially those typically seen after long line hook-and-release incidences (mouth and foreflipper hooking). Currently it is unclear how embedding barnacles affect the healing of anthropogenic-borne wounds on sea turtles, if at all. These two genera also embed themselves into fibropapilloma tumors.

The pictured hawksbill appears to be healthy, and obviously spends some degree of it's time in the pelagic environment - as evidenced from the occurrence of gooseneck (Lepas) barnacles on the carapace. The load of epibionts in generally is not uncharacteristic of similar sized hawksbills elsewhere, and I see no reason why it should be kept in captivity to remove barnacles." - Michael Frick, PhD

Leeches

Only two species of leeches are found on the Atlantic coast:

-

- Ozobranchus margoi affects loggerheads but has been reported on others.

- Ozobranchus brachiatus affects green sea turtles and has been suggested as a vector for the fibropapilloma virus.

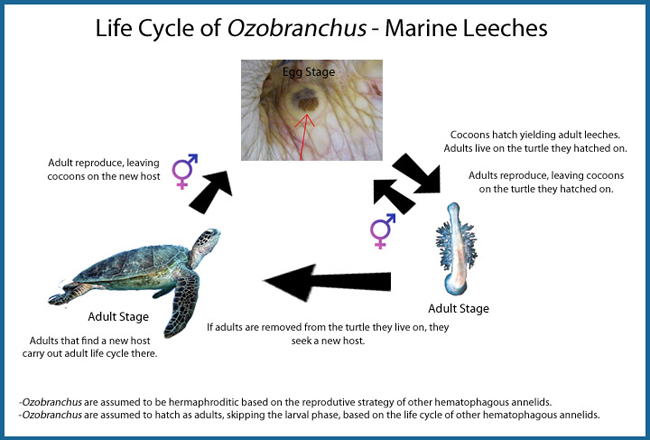

Ozobranchus (Marine leeches) are jawless leeches with a well developed, bell shaped anterior sucker. Infestations are readily apparent in areas where the dermis is thinnest, such as around the eyes, corners of mouth, and cloaca. Symptoms include weakness and lethargy due to loss of blood. Placing a sea turtle in a fresh water bath for 4-6 hours will remove adult leeches. Eggs must be scraped off or will hatch adults in 2-4 weeks.

Leech facts:

- Leeches are hermaphrodites (they are both male and female).

- They are true parasites that feed on blood by puncturing the skin with a sharp proboscis.

- They secrete the anticoagulant hirudin to prevent clotting and allow continuous feeding.

(Graphic provided by Brandon Monastero)

Endoparasites

Internal parasites are common in sea turtles. Harm may be done to the host by the adults as well as by the immature stages of the parasite.

Protozoans

These are single celled organisms that have been described in sea turtles. Records show that amoebas and coccidia have been implicated in the death of green and loggerhead turtles. Oocytes can be found in apparently healthy turtles so it is not known if these infections are “sub-clinical” or opportunistic pathogens.

Infections may involve the liver and intestinal tract although these organisms have been noted to cause infection in the central nervous system in other species as well.

Treatment is with Flagyl (metronidazole) or other coccidiostat medication.

Cestodes

Tapeworm infection has not been reported in sea turtles.

Nematodes

Nematodes are true worms (helminths) which infect the GI tract. Some species such as Sulcascaris can affect many different species of sea turtle. Nematodes can cause a mild ulcerative enteritis, but if found in large numbers, they can result in severe inflammation.

The adults live in the gastrointestinal tract and pass their eggs in the feces of the turtle. These negatively buoyant eggs may then be ingested by mollusks which serve as intermediate hosts. Route of infection may also be direct ingestion of eggs.

Green turtles do not typically get nematodes unless fed an artificial diet, but they are common in loggerhead turtles.

Treatment is with Panacur (fenbendazole).

Acanthocephalans

Spiny headed worms found in intestine. No clinical signs reported.

Trematodes

There are many species of flukes, some may cause sub clinical disease and others may be life threatening. Flukes may affect various tissues.

Sea turtles may become infected with flukes by ingesting cercariae rich intermediate hosts. These flukes may then live in the intestinal tract. Heavy infections can severely debilitate the host.

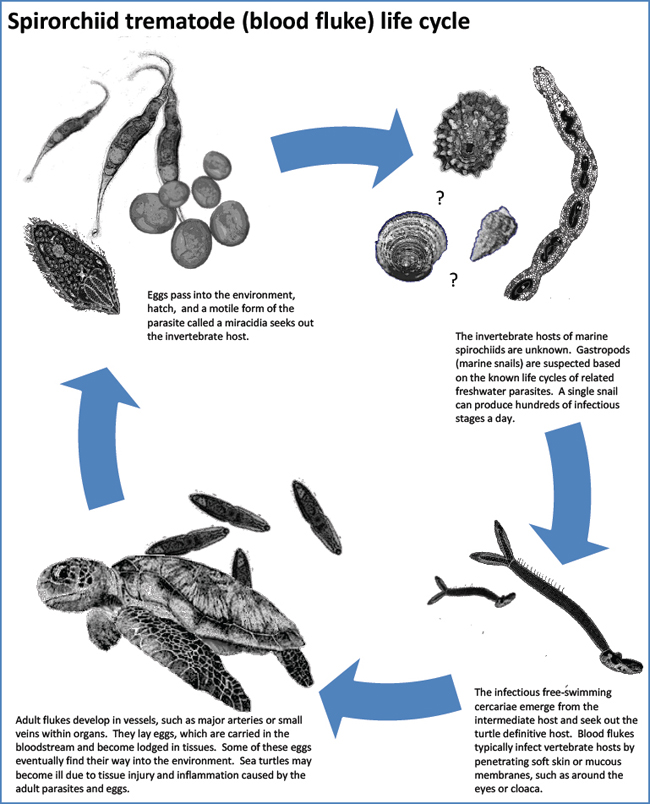

Spirorchiid trematodes (blood flukes) are the most damaging type of fluke. The adults live in the vascular system and can deposit vast numbers of eggs into the bloodstream. The eggs commonly lodge in the brain, liver, kidneys, lung, and intestines. They can cause a granulomatous reaction whereever they are deposited.

The most debilitating of the four common genera of trematodes is Haplotrema spp.

Trematode eggs are negatively buoyant and can be found in the feces of infected turtles. A blood test for adult spirochids is available.

Treatment is with Droncit (praziquantel).

The life cycles of marine spirorchiids have yet to be discovered. This graphic is based on extrapolation from

known life cycles of related parasites, which use a single intermediate invertebrate host and a definitive

vertebrate host. Both hosts are required for the parasite to survive and reproduce.

(Graphic provided by Dr. Brian Stacy)

Resources

A Synopsis of the Literature on the Turtle Barnacles PDF

Distribution Patterns of Epibionts on the Carapace of Loggerhead Turtles PDF

This chapter should be cited: Mettee, Nancy. 2014. Parasites. Marine Turtle Trauma Response Procedures: A Veterinary Guide. WIDECAST Technical Report No. 17. Accessed online [date].

Updated 3/2014