Selected Surgical Techniques

Please review the section on Anesthetic Protocols before attempting any surgical procedure as the needs of sea turtles are quite specific.

Note:

-

-

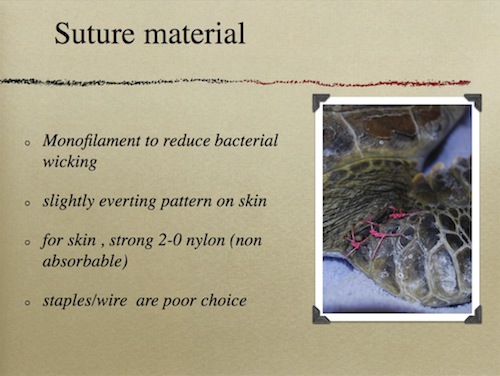

Due to the potential wound contamination from the patient and from the environment, monofilament suture is used whenever possible.

-

Disposable, waterproof drapes are best for surgery as frequently the drape becomes very contaminated. Ideally, adhesive drapes should be used.

-

Dr. Wyenken’s "The Anatomy of Sea Turtles" is a must for all surgeons in order to orient themselves to the anatomy that they will encounter. PDF (27MB)

-

All surgeries in sea turtles are clean contaminated, contaminated, or simply dirty. To reduce the chance of infection the following are employed:

- Perioperative and post operative antibiotics

- Copious lavage of surgical site with warm saline

- Multiple surgical packs allowing for change of instruments once the intestinal tract is closed

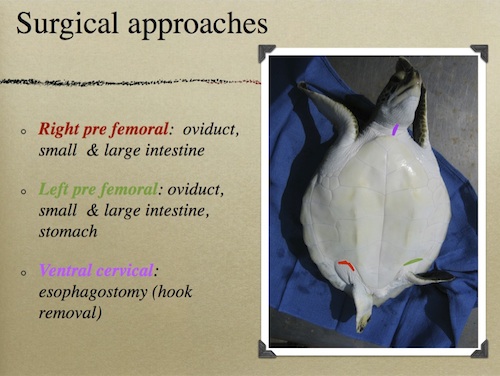

Exploratory coeliotomy requires both left and right prefemoral approaches to evaluate the entire length of the intestinal tract. If a hook is present in the esophagus, and is suspected to be attached to line that extends into the gut, the esophagostomy should be done first followed by the left prefemoral, then right prefemoral approaches. Rarely is a surgeon so certain that no monofilament or other cause for concern is present that a single coeliotomy is warranted.

A TRANSPLASTRON APPROACH FOR COELIOTOMY IS NOT RECOMMENDED FOR SEA TURTLES AND CAN RESULT IN FLAP DEVITALIZATION AND COMPLICATIONS DUE TO PROLONGED HEALING TIME.

Esophagostomy

The ventral cervical approach is commonly used for hook removal. Incisions made within 1 cm of the plastron will essentially be stabilized (fixed) at one end and will have a decreased risk of dehiscence. Incisions made in the mid cervical region will be subject to a great deal of tension as the neck is moved about during recovery/convalescence and will have increased risk of dehiscence. If an incision must be made in the mid cervical area, use of stents to overlay the primary suture line is recommended. The esophagus is very elastic and once isolated can be manipulated toward the skin incision for hook removal. The esophagus passes slightly dorsal and to the right side of the trachea. The sea turtle esophagus lacks distinct constrictions but does contain esophageal papillae. These papilla are oriented rearward and can be sharp due to keratinization.

Once anesthetized, the ventral cervical region of the neck is prepped with betadine scrub and rinsed with saline to remove the suds. (Alcohol is not used in surgical preps due to rapid cooling from evaporation and potential skin irritation.) The surgical site should always be prepared so that the incision can be extended if needed. The area should be toweled and draped with water proof drape material.

The dermis is very thick, so a scalpel is required to incise as a CO2 laser does not penetrate well. The subcutaneous tissues are quite elastic. If the turtle is in good body condition, the fat stores may be quite extensive. A combination of blunt dissection (for muscle bodies) and sharp dissection (for fibrous connective tissue) will be needed to expose the esophagus. Slow progress in this area will ensure that blood loss is minimal.

Once the esophagus is identified, it can be freed up from supportive tissue to allow for greater manipulation. If monofilament line is attached to the hook, it can be used to help identify the precise location of the hook. An assistant can grasp the line and apply light tension, allowing the surgeon to isolate the movement.

When the esophagus is exposed, stay sutures are placed in the serosa both cranial and caudal to the proposed incision site. The esophagus is extremely elastic, so an incision is quite challenging if tension is not applied while cutting. A scalpel is used to sharply incise the esophagus between the stay sutures, directly over the hook.

After the esophagus is opened, the esophageal papillae are apparent. These conical projections ensure the passage of food from the mouth to stomach. Locate the hook and visualize your situation. Hooks typically have oxidized (black) material associated with them and frequently have bait still attached. If there is monofilament extending down to the stomach, you may attempt to gently pull it towards you, but if resistance is met with, it is best to cut the line and focus on the hook.

Single barb hooks may be cut with pin cutters to facilitate antegrade removal. Do not attempt to back out a hook as it will cause more damage to the soft tissue. The least traumatic way to remove a hook is to advance the barb through the tissue using an instrument. Hooks are very sharp and will easily puncture a glove. The eye of the hook may be cut off with pin cutters at any time to reduce drag through the tissue.

New style long line “circle hooks” may be impossible to remove in an antegrade fashion. These can be removed by incising the esophagus from the lumen side over the barb and backing the hook out in a retrograde motion. This will cause more tissue damage and may require closure of the esophagus in several areas.

Treble hooks, or multi-barb hooks, cannot be removed in an antegrade fashion. Fortunately, it is rare that all barbs are embedded. Assess the situation and attempt to remove the hook with as little trauma as possible.

Once the hook is removed, the esophagus may be closed in an inverting, continuous (cushing) suture pattern. Take care to tuck the papillae into the lumen of the esophagus. A suggested suture material is Monocryl 3-0 (an absorbable monofilament suture).

After the esophagus is closed, copious lavage of the surgical site with warm saline and a change of contaminated instruments is needed to reduce the risk of post operative infection of the area.

The muscle bodies and subcutaneous tissues may then be closed with a simple continuous pattern. An intradermal or subcuticular suture line is buried beneath the dermis in a simple continuous pattern. The dermal closure may be accomplished with 2-0 or 3-0 Ethilon (non absorbable, monofilament suture). Stents are often used to support the primary dermal closure layer. The stents may be removed in 2-3 weeks. The primary dermal layer may be removed in 4 weeks.

The suture line should be inspected weekly and debrided as needed. Post operatively, esophagostomy patients are dry docked for 12-24 hours until they show sufficient strength to be returned to the tank. The turtle is not fed for 24 hours to prevent stretching the inflamed esophagus until a seal has formed.

Post operatively, esophagostomy patients are dry docked for 12-24 hours until they show sufficient strength to be returned to the tank. The turtle is not fed for 24 hours to prevent stretching the inflamed esophagus until a seal has formed.

Prefemoral Approach for Coeliotomy

Place the patient in dorsal recumbency. A tilting table may facilitate exposure. The hind flippers can be taped into a clasp position for improved exposure of the inguinal fossa.

Once anesthetized, both sides of the inguinal fossa should be prepared for surgery. The dermis should be prepped with chlorhexidine or betadine scrub and rinsed with saline to remove the suds. (Alcohol is not used in surgical preps due to rapid cooling from evaporation and potential skin irritation.) The surgical site should always be prepared so that the incision can be extended if needed. The area should be toweled and draped with water proof drape material.

A curvilinear incision is made in the dermis following the arc of the plastron. Once the skin is incised, the subcutaneous tissue can be identified and vessels ligated if needed. In thin or emaciated turtles the inguinal fat stores may be very watery and easy to blunt dissect through. In patients with adequate fat stores a combination of blunt and sharp dissection is used. In sub adult and adults it is possible to avoid transection of any muscle bodies and identify the coelomic lining in this area. The coelomic lining is membranous and avascular. Stay sutures should be placed on the lining to act as retractors and ensure that each layer may be closed individually. Sharp dissection will be needed to open the coelomic lining and if an obstruction or foreign body is present large amounts of free fluid are frequently present. If this fluid is contaminated with fecal material euthanasia may be a more humane option as the coelomitis is associated with high mortality.

The left prefemoral approach allows access to the left oviduct, much of the small intestine and the stomach.

The right prefemoral approach allows access to the right oviduct, much of the large and small intestine.

The viscera can be teased out of the incision for visual evaluation. While exteriorized the tissue should be kept moist with saline soaked laparotomy pads. Typically, sections of intestine are exteriorized, evaluated, and then returned to the cavity. With steady progression, most of the gut can be evaluated in this fashion. Enterotomies to remove liner foreign bodies or intestinal resection and anastomosis can be performed while the section is exteriorized. Once the surgical sites are checked for leaks by injection of saline, they may be returned to the coelomic cavity with gentle pressure.

Once all the available viscera have been evaluated on one side, the second prefemoral coeliotomy can be performed. This may be a quick evaluation to insure no further problems exist or it may be as involved as the first. At this point it can be determined if the entire gut has been examined or if there are sections that are inaccessible.

Three layer closure, coelomic lining, subcutaneous, and dermal are appropriate.

This chapter should be cited: Mettee, Nancy. 2014. Selected Surgical Techniques. Marine Turtle Trauma Response Procedures: A Veterinary Guide. WIDECAST Technical Report No. 17. Accessed online [date].